The Influence of Collaboration on Understanding

Inez Hohn

Inez Hohn student-taught at the Fishback Center for Early Childhood Education, the lab school at South Dakota State University. She now teaches Kindergarten at Freeman Academy in Freeman, South Dakota. Inez enjoys finding new ways to engage her students each day as she learns from them. She recently received the Early Childhood Student of the Year, awarded by South Dakota AEYC.

Introduction

How do children learn, not only from experience, but also from each other? How do children co-construct meaning? As a student teacher, these questions informed my work as I facilitated an inquiry of towns and maps with a small group of four and five-year-old children that spanned two months. The four children possessed varying dispositions, skills and background knowledge, which they brought to the investigation.

Map Making

In our initial mapmaking, the children illustrated scenes and buildings that were important to them. Their maps reveal how they viewed the world and what they thought of when imagining a map. They included places we had talked about; for example, Margaret focused on her house, a playground, roads and stop lights. Oliver included houses, farms and playgrounds. Some had roads while others did not. This presented the opportunity to look into how roads are represented on maps.

While there are roads in Margaret’s map, she focused more on scenic aspects such as houses and a playground.

Oliver’s map is a specific scene which includes grass, trees and farm buildings.

An Exchange of Ideas, Resources and Actions

We continued with an exchange of ideas. To elevate the idea of roads on maps, I brought in a variety of road maps and posed ideas and questions. The children responded and crafted interpretations. In turn, they located towns and used their fingers to trace roads, pretending to drive from place to place. They associated roads with traveling and used past experiences to make sense of characteristics of roads, such as how they connect places and that the curvatures matter for smooth driving. They brought their experience to the discussion and in doing so talked about places they had traveled, referencing the maps in front of us. The conversation focused on their hometown, Brookings. They branched out to talk about places they had traveled, such as Sioux Falls, a major nearby city.

Looking at road maps

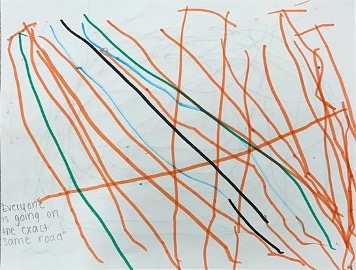

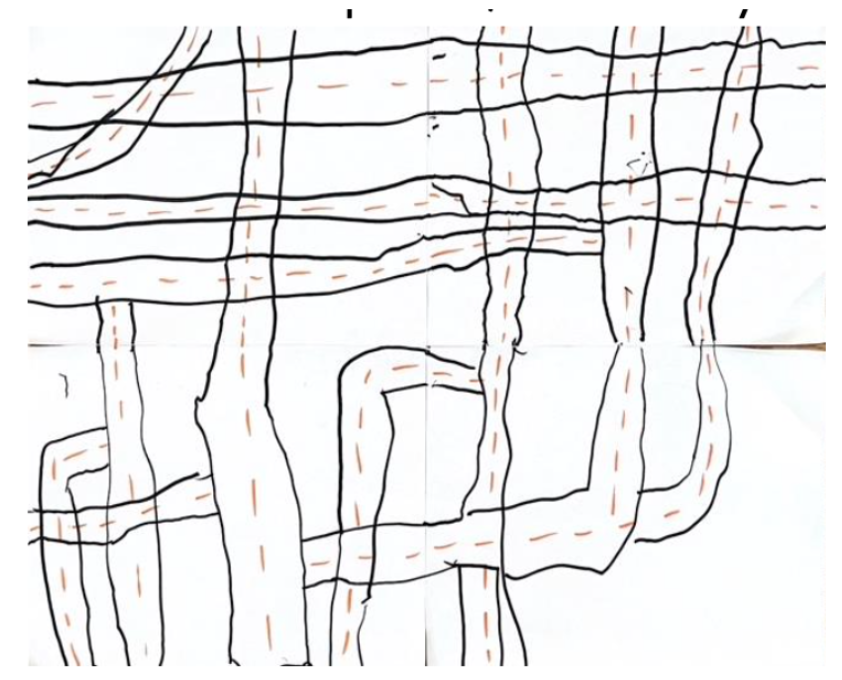

When we revisited map-making, the children focused on the roads. The children took what they noticed from examining the published map and transformed their maps to include more prominent roads. I noticed a deeper understanding in their discussion of road function and representation on maps. From this point, all the children added roads to their maps. One map focused on having straight roads and the child resisted using circular and curvy roads. Their reasoning was to make sure people traveling through the town didn’t get sick from all the loops.

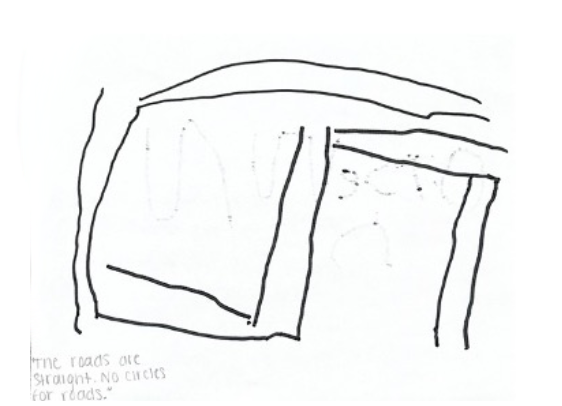

“The roads are straight, no circles for roads.” -Oliver

“It’s a straight-line road and then you go left and right. When people are walking, they have stop signs.” -Cora

They focused on including spacing between roads and logical paths to ensure that travel from place to place was possible. They took these ideas directly from the experience of their fingers driving on the printed road maps. Travel became the purpose of roads.

Margaret made sure to make all the roads connected for smooth travel.

Oliver focused on having straight roads with corners so there were no loops.

As we walked around campus, I pointed out the use of sidewalks to travel. The children made the connection that sidewalks were similar to roads. Henry labeled the sidewalks as “walking roads,” which opened up another meaning-making conversation. The group noticed the sidewalks as college students walked past them. They contrasted walking and driving in their analogies.

We had some experience with 3-D maps when we used Google maps to get a street view of places in our town. We changed our perspective by switching between street view and aerial view, which allowed us to get a better idea of locations. To navigate our walk, we referenced a 2-D map of the SDSU campus in which the buildings were drawn to appear three-dimensional. They explored their surroundings making connections between where they were and their location on the map. They again followed the pathways with their fingers. This time, they traced our walking journey. The children noticed the aerial view and realized the connection between sidewalks in aerial view and the same sidewalks in street view. The children’s conversations deepened over time. Their understanding of maps evolved, highlighting their growing understanding of the concepts of travel, how travel flows, the purpose of roads and sidewalks and finally how they are represented.

.

.

The children traveled along the sidewalks as if driving on roads.

Meaning-Making

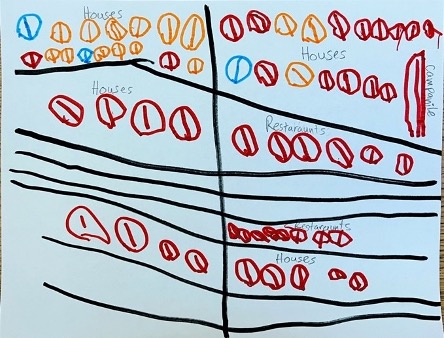

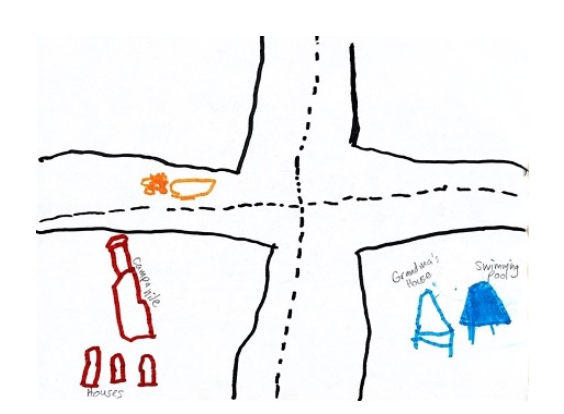

Through these interactions and exchanges, children’s perspectives shifted. Still working independently, they created a third map, increasingly aware of each other's efforts. Their experience of finger tracing the road maps, their campus walk and what they learned from each other was evident in their third map, which included more elaborate buildings and roads with more connections. They focused on the pathways that connected places and highlighted movement between places. Then, the children worked to solve the problem of representing buildings that fit between connected roads.

Margaret drew the roads first, focusing on leaving room in between them for buildings.

Oliver created an intersection which left room for buildings.

In these drawings, I saw the give and take between their experiences and their growth in knowledge. When I revisited and reflected on this inquiry process, I found that each child influenced the others through common themes, such as landmarks, representing roads, and including space for buildings and homes.

The children’s ideas about maps developed as they participated in activities, drawing and conversations. They included the purpose, flow and visual representations that are apparent in maps and formed their own versions. Through each step, they made sense of their experiences as they constructed together what maps meant to them. Although they developed individual interpretations, their experience deepened as they collaborated.

Collaboration

This inquiry continued for another three weeks. As the project progressed, I called them to work together on parts of the town.

The children collaboratively drew a new map that they later built into a three-dimensional town.

Reflection on My Learning

I reflected on our inquiry project and noticed a process had unfolded. I brought information in the form of activities, materials and experiences and the children made meaning. At the same time, the children brought their ideas to the conversation and formed meaning from what their peers shared. I then crafted my plans to fit what I saw and heard from the group. This shifted the path of our inquiry and sharpened my attention to what the children said and did, ultimately allowing me to better support their engagement and enrich their learning.

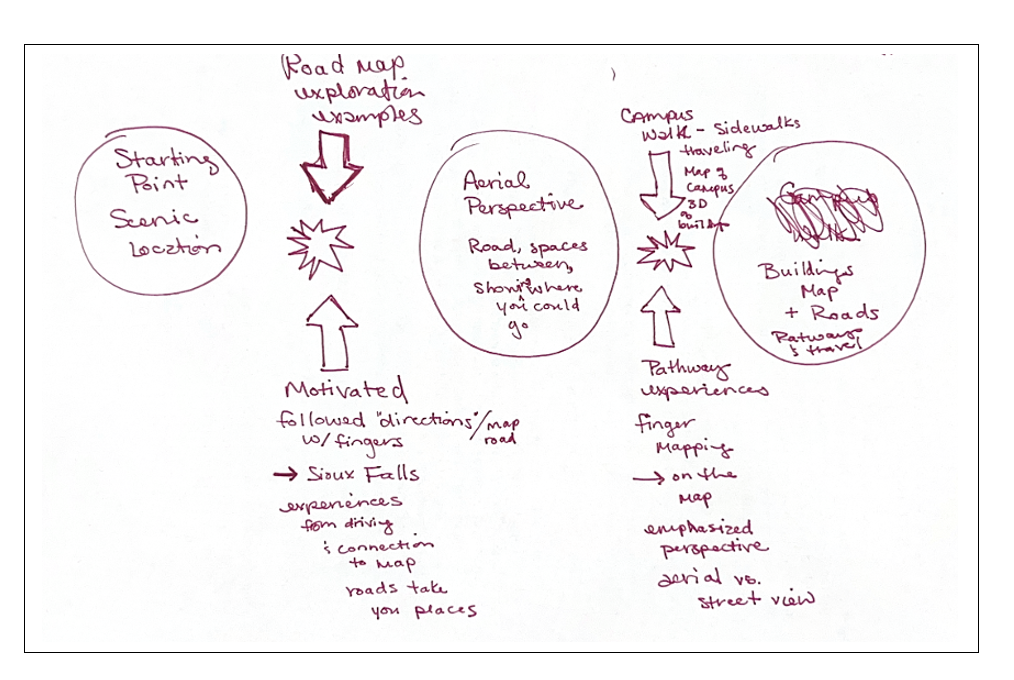

The children learned to collaborate through this inquiry. I, too, collaborated, creating an idea map (below) with my mentor that outlined aspects of our journey. The graphic provided a visual representation of our process, promoting further reflection.

I found a deeper understanding of the interactions that occurred between the children and I, including the energy bursts that occurred among us. When I pay close attention, I can see the growth of children's thinking more clearly and respond to it.