From the early 2000s, Roberta has held workshops and courses about the creative use of artistic, natural and recycled materials, especially for educators and teachers, collaborating with social cooperatives. She then spent seven years working as an atelierista in a Reggio-inspired preschool, in addition to one year at the Loris Malaguzzi Center of Reggio Emilia, with study groups from all over the world. Currently, she works primarily as a consultant for personal and professional growth.

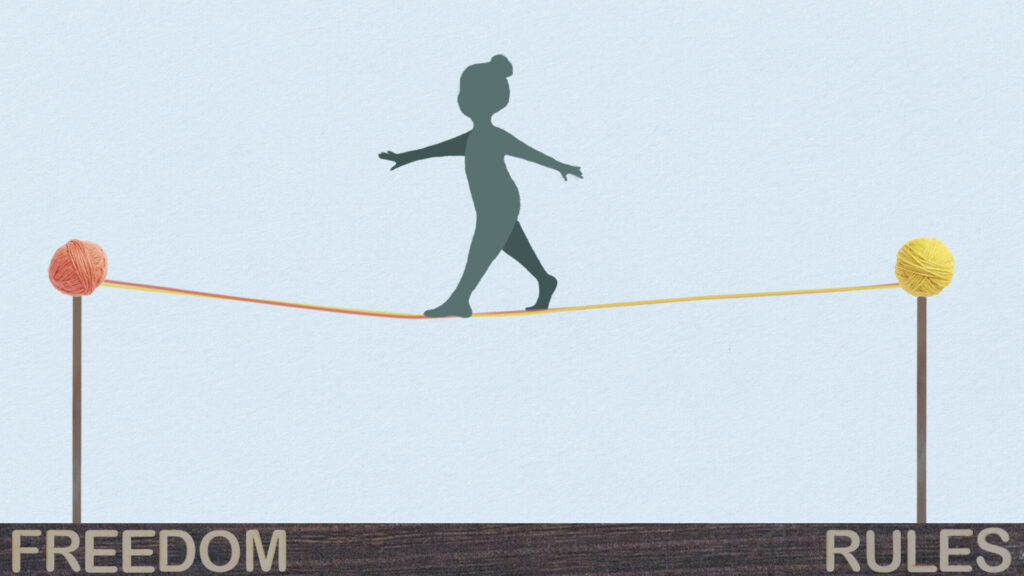

How does one find the right balance between rules and freedom, in order to support the creative process?

The image above is part of a 100 x 70 cm composition made by three five-year-old children with some loose parts. How do you think the creation process developed? What was the proposal (if any) and the role of the adult? First of all, consider it was the last of a series of atelier sessions dedicated to these materials.

This is quite significant, since the first time children meet a new material, they like to freely explore it for a long enough time, to know its potential and limits. So it’s better to postpone more specific proposals. But let’s start from the beginning.

I would have liked to offer an experience with loose parts – small pieces of plastic, metal, wood, cardboard, buttons, stoppers, scraps from industrial and artisan processing – all collected in various containers. But how to present them? As a completely free exploration? I could imagine how inebriating the wealth and multiplicity could become, a confusing jumble in a few seconds... So how to “contain” children’s activity and stimulate a rich personal research at the same time?

My solution was a kind of game with a few simple rules: a small group of children at a time, the materials neatly arranged on a table. Every child had a small container which they could use to “shop” for their chosen materials. On other tables, there were white cardboard bases, where children “played” with their materials.

Once the game (and the composition on the cardboard) was finished, the children could optionally take a picture of the final composition and give it a title. Then they put all the used materials back into their personal container and divided them in the different respective containers. At this point, children could start the process again and again.

Another solution I tried is putting all the containers in the center of a large table, where the children could take the materials they needed from time to time. Maybe it was my need of order... Anyway, it worked. The rules were gladly accepted as part of a game and allowed children to manage themselves independently, respecting individual times. Even the final step of “destruction” of the work was “naturally” welcomed by children, immersed in a fast and intense research, without needing to “hold” a result. A demonstration of how the “attachment” to the product is more frequent in adults than children.

As the children liked it very much, we repeated the same activity several times and I gradually introduced some variants, for example cardboard bases of different formats or a selection of a certain range of materials (according to tactile, chromatic or other criteria). Some variations were stimulating for children, others were not. So I chose the next variant observing children’s responses. It was also interesting to observe how different materials influenced the composition and, at the same time, how the personal style of each child was recognizable through the diversity of materials: personal style and material characteristics are elements that are always intertwined in every work.

As a last step, I proposed a group work: three children at a time, on a large format of 100 X 70 cm. Of course I knew that the format was too big to be “controlled” and organized with a shared project a priority. So I invited the children to start individually, from the side they preferred. Then each group followed a process that organically unfolded, bringing the various contributions together. Inspired by the forms that were gradually created and by some questions of mine, children gradually connected the three parts, both aesthetically and narratively. In this case, I proposed to fix the final composition on the sheet with glue, as a tangible conclusion of a long process and enhancement of a collective work. Product and process are both important: it’s up to us to understand when it’s time to focus on one rather than the other.

Every game has its own rules, which are willingly accepted by those who freely choose to play. Sometimes the rules “allow,” sometimes they “limit,” as well as total freedom can be an obstacle or an impetus for the creative process. There are no solutions that are always good. Each time we have to look for the right balance, taking into account the context and the objectives. It is a flexible dance between two necessary opposites. Listening empathically to children can help us be attuned to their rhythm.

Reprinted from: https://www.robertapuccilab.com/the-grammar-of-matter/playing-with-unstructured-materials/ Look here for more articles from the Roberta Pucci Lab:http://www.robertapuccilab.com